More than just a venue for the Commonwealth Games and professional sports—A brief history of Commonwealth Stadium's 40 year legacy.

106th Grey Cup

From November 21–24, thousands of visitors flocked to downtown Edmonton to take part in the Grey Cup festival and parade. The excitement culminated with the 106th Grey Cup championship game on Sunday November 25, at Commonwealth Stadium.

The 106th Grey Cup was named Canadian Sport Event of the Year!

Commonwealth Stadium 40th Anniversary Celebration

On September 8, 2018, the City of Edmonton celebrated Commonwealth Stadium's 40th Anniversary at the Edmonton Elks football game. The City hosted a post-game video production, laser light show, fireworks, and on-field dance party following the Edmonton Elks rematch game against Calgary. Thank you for joining us in celebrating 40 years of top-tier professional sports, concerts and events at Commonwealth Stadium!

Light the Stadium

Commonwealth Stadium is a new beacon of light in the City! In 2018, Commonwealth Stadium unveiled all new exterior lighting to celebrate the facility’s 40th Anniversary, and as a legacy to the Stadium.

Edmonton's Stadium Legacy

By Michael Payne, City Archivist

Photos: City of Edmonton Archives

Clarke Stadium was used for more than just football. It had a track and in 1947 Edmonton hosted the Canadian Track and Field Championships. The Edmonton Bulletin took lots of photographs, including this action in a women's hurdles race. In the late 1920s, a number of Edmontonians began a campaign to convince the federal government to give up a large 95 acre tract of land in east central Edmonton for a new athletic park. The land had been used briefly for a federal penitentiary until World War I, when the prison closed, and for the next decade the land and buildings remained largely unused.

The city acquired 26 of the 95 acres on a long-term lease in 1930. A plan of the area from 1930 shows baseball diamonds, rugby football and soccer fields, a cricket pitch, and sports ground with a cinder running track on the land. Joseph A. Clarke led the campaign for the sports field, and by 1935 as mayor of Edmonton, he was in a position to push an even more ambitious plan for a stadium and athletic park forward.

This plan required considerable funds and a lot of lobbying to secure support from different sports organizations. Newspaper reports in 1938 indicated that the city had spent about $46,000 on the various facilities in the park, including recent expenditures of about $7000 for a football stadium with bleacher seating for 2,040 people, dressing rooms for home and visiting teams, and parking for spectators' cars. The following year City Council paid for floodlights, and the Edmonton Eskimos' first home game under the lights in 1939 brought in a gate of $800 – 16% of which went to the city!

The new stadium was named Clarke Stadium after the former mayor who had done so much to make the athletic park possible.

The popularity of football continued to grow, and after World War II, a largely professional football league, the Western Interprovincial Football Union, attracted teams from several cities in western Canada. In 1949, the Edmonton Eskimos joined this precursor to the West Division of the Canadian Football League.

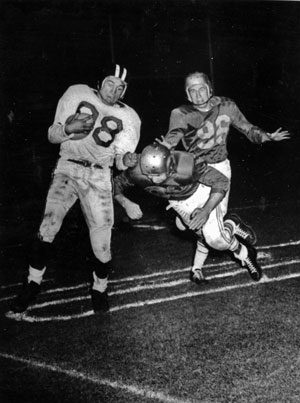

Football was the most popular sporting activity at Clarke Stadium and the Eskimos were Edmonton's team. This dramatic photo was taken at a 1954 game between the Eskimos and the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. In the early 1950s, seating at the stadium was expanded almost every year. In 1954, a new west grandstand was built raising seating capacity at the old stadium to 20,667. In 1961, the stadium was expanded again when the east grandstand was built, raising total capacity by another 5,500 seats. Unfortunately the stadium which also hosted track and field events, high school football games, and other sports, was showing its age. When Edmonton was selected to host the 1978 Commonwealth Games, brief consideration was given to completely refurbishing Clarke Stadium before a decision was made to build a completely new, significantly larger venue beside the old stadium. Work began on the new Commonwealth Stadium in 1976, and the Eskimos played their last game at Clarke Stadium (a 14-8 victory over the Winnipeg Blue Bombers) in August 1978.

A smaller, refurbished Clarke Stadium continues on in use as a secondary sports venue hosting high school and amateur sports teams literally in the shadow of its larger neighbour, Commonwealth Stadium.

In the early 1970s, a group of Edmonton sports enthusiasts organized a bid to host the 1978 Commonwealth Games. The group quickly secured significant federal, provincial and city support for the bid. The financial backing given to the bid committee was an important factor in Edmonton being granted the games, and key component of this support was a proposal to build or renovate a range of venues as a sports legacy for Edmonton.

Initially, there was some thought given to rebuilding Clarke Stadium to make it large enough to host the main track and field, and other sports events for the games. However, by late 1974, there was substantial agreement that a new larger stadium was the best option. There were some debates over the form that stadium might take and discussions around possible locations, but by January 1975, Edmonton City Council had settled on construction of a huge, over 40,000 person capacity, stadium adjacent to the old Clarke Stadium.

Construction of the new Commonwealth Stadium was a massive undertaking. This photograph, taken in August 1976 shows work on the excavations for the field level and the start of work on the recreation centre and field house at the south end of the stadium. In addition, Council approved construction of the Kinsmen Aquatic Centre for swimming and diving events, and the Argyll Velodrome for cycling, while badminton, wrestling and some other sports would be staged using University of Alberta sports facilities.

Despite considerable opposition from residents and community groups in the new stadium area, construction began on the new facility in March. Edmontonians were regularly informed by the news media about the scale, and cost, of the project. Construction required removal of 500,000 cubic yards of dirt for the stadium infield. This excavation work required 40 trucks, eight earth movers, backhoes, excavators, and other heavy equipment.

The construction was not without problems. There was a lot of interest in an extra bill of $50,000 for a special Royal Retirement Room adjacent to the Royal Box, and some questions were asked about the training and office space allocated to the Eskimos. There was even a long and often heated debate about whether or not the stadium needed a roof or dome to make it impervious to the elements. The projected cost of $18.2 million (or more) for the roof limited public support for this idea. By early 1978, these issues seemed resolved, though there was some concern expressed by a few athletes about footing on the Pro Turf surface used for the track, and for some field events such as javelin and high jump. Otherwise, the stadium and other facilities were finished in good time, more or less on budget, and with minimal controversy.

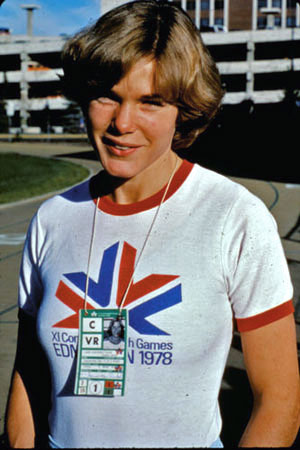

Diane Jones-Konihowski was one of Canada's best-known and most successful female athletes in 1978, and she lived up to high national expectations by winning the pentathlon. The Commonwealth Games were officially opened by Queen Elizabeth on August 3, 1978. In total 1,474 athletes and 504 officials from 46 Commonwealth countries participated. Edmonton swelled with pride for hosting such a large and exciting sporting event. One newspaper report suggested after the grand opening that the "...moment seemed suspended in time. There was an atmosphere of quiet pride, friendship and expectation. It was a mental high that would never be repeated."

The mental high of the reporter was matched by 10 days of sporting highs as well, from the official opening on August 3, to the closing ceremonies on August 12. A total of 395 medals were awarded in 128 separate team and individual competitions. Canada, as host country, sent a particularly large and well-prepared team to the games, and for the first time, Canada led the overall medal count over traditional Commonwealth sporting powers such as Australia and England. In total, Canadian athletes captured 109 medals, or just over a quarter of all medals awarded. This unprecedented medal total also included 45 gold medals, meaning Canadian athletes finished first in about one third of all the games competitions.

Day after day, the sports pages were filled with accounts of new Canadian sports heroes, and few new international stars as well. Among others, Debbie Brill, Diane Jones-Konihowski, Greg Joy, Elfi Schlegel, Jocelyn Lovell, Gordon Singleton, Graham Smith, Janet Nutter, and Wendy Quirk, all distinguished themselves at the Edmonton games, as part of their long and notable international sports careers. Fans of athletics, swimming, diving and other sports would also watch a number of well-established or emerging international stars such as Daley Thompson of England in the decathlon, Henry Rono of Kenya in a number of running distance events, and Australian swimmers Tracey Wickham and Michelle Ford.

A major feature of the Commonwealth Games bid, and one of the reasons why Edmontonians were so supportive of the idea of hosting the games, was the prospect of a legacy of first-class sports venues in the city. Although the Games Committee struggled to keep costs down, and some criticism was leveled by athletes and officials at the Commonwealth Stadium track and other facilities, by the end of the games most felt that the venues and organization of this massive undertaking had been excellent.

When the Commonwealth Games flag was raised at the opening ceremonies on August 3, 1978, the long years of planning, fundraising and construction were finally complete. New construction for the games included some new venues such as the Kinsmen Aquatic Centre, which has remained a major centre for competitive swimming and diving as well as one of the city's most popular fitness and leisure centres. The Commonwealth Lawn Bowling Green was also built for the games, as was the Argyll Velodrome and Strathcona Shooting Range. Other existing facilities were refurbished to host portions of the competition. The Northlands Coliseum was the venue for gymnastics, the Jubilee Auditorium hosted weightlifters instead of travelling musicals and high school graduations, and the University of Alberta's arena and gym were used for badminton and wrestling.

However, the jewel in the Commonwealth Games crown was the Commonwealth Stadium, which hosted athletics, and the opening and closing ceremonies. Immediately after the games, it became home to the Edmonton Eskimos as Clarke Stadium was replaced as the team's home field. The stadium was one Canada's largest, and other teams such as the Edmonton Drillers soccer club used the stadium as well.

So successful were the Commonwealth Games, that Edmonton chose to host another international sporting event – the Summer Universiade Games in 1983. This event featured student athletes from around the world (totalling approximately 2,400 athletes from 73 countries), but it failed to capture the public imagination quite the same way that the Commonwealth Games did. It did have one major legacy for Commonwealth Stadium however, which was expanded by about 18,000 seats to a total capacity of just over 60,000 people. Additional seating can be added, and 62,531 people attended the 2002 Grey Cup game at Commonwealth.

With the new seats, Commonwealth became Canada's largest permanent stadium. As a result it has become a favoured site for large international events such as the 2001 IAAF World Championships in Athletics, the 2002 FIFA Women's U-19 World Cup of Soccer, the 2005 World Masters Games, the 2006 Women's World Rugby Cup, the 2007 FIFA Men's U-20 World Cup of Soccer, and it is often used by the Canada Men's National Soccer Team as a home field. Commonwealth has hosted the Canadian Football League Grey Cup in 1984, 1997 and 2002. It has even been used for outdoor hockey, the 2003 Heritage Classic Hockey Game featuring the Edmonton Oilers and the Montreal Canadiens.

Much of the appeal of the stadium for soccer, rugby and football teams is that it is still a natural grass field. Over the years, ideas of "improving" the stadium with artificial turf and a dome or roof have kept being raised, but traditionalists have won out so far, and Commonwealth remains a grass field stadium open to the elements of Edmonton's capricious northern climate – so you can still freeze the field for hockey or shiver through a late November Eskimos game just as people did at Clarke Stadium in 1938.

When the City of Edmonton acquired land for a stadium complex in 1930, the idea was to create a range of facilities that citizens could use for multiple sports or just for recreation. Clarke Stadium was just part of a larger complex of recreation facilities on the site, and when Commonwealth Stadium was initially proposed, Edmontonians were encouraged to see it as more than just a venue for the Commonwealth Games and professional sports.

North central Edmonton had relatively few sports and recreation facilities, and the Commonwealth Sports and Fitness Centre was an important addition to the overall stadium plan. The Sports and Fitness Centre was designed to offer fitness equipment and classes, racquetball and squash courts, as well as a gym to citizens of all athletic interests and abilities, but it was also meant to be used as multi-purpose space as well. Over the years its meeting and banquet rooms have been used for just those purposes as well as for craft shows, community events, and even the Canadian Football League Schenley Awards.

The stadium is also a popular venue for large outdoor events including major concerts. Over the years, a series of bands with enough popularity to fill a stadium have performed at Commonwealth including the Rolling Stones, the Police, U2, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, Tim McGraw, Willie Nelson, the Lilith Fair, Edgefest, and many others.

Most people associate Commonwealth Stadium with major football and soccer games or with international events such as the Commonwealth Games or the World Championships in Athletics, but concerts, meetings, recreational activities, and classes for the community are also a major part of Commonwealth's legacy.